What is stress?

Stress is our body’s response to a demand placed on it. Stress is often confused with anxiety, but stress is not a diagnosable mental illness. Stress is a normal condition, experienced by everyone. It involves an emotional, physical or mental response to a change in our environment (stressor), which can be positive (eustress) or negative (distress). The stress response can cause bodily or mental tension, and can be thought of as a state of readiness - the fight or flight response. A small amount of stress from time to time is not a problem, it can even motivate us to get things done. But when stress is intense and ongoing, it can start to impact our physical and mental health.

Experiencing stress

Stress has a thinking part and a feeling part. When stressed, you might have thoughts like “I can’t cope with this”, “this is too much pressure for me”, “I don’t have enough time” and “how am I going to get this done.” The impact of the source of stress exceeds the resources you have available to cope. In essence, your mind has decided you have ‘more on your plate than you can chew’ - this is the thinking part of stress. At the same time, your body goes into ‘fight or flight’ mode. Your nervous system is activated, and hormones are released that enable you to react quickly. For example, when stressed you might notice your heart rate increases, pupils dilate, breathing rate increases and muscles tense. You might also notice changes in mood or emotions. These changes enable you to deal with the situation. Prolonged stress seems to have a greater effect compared to acute or transient stress on the body’s immune response. This change in immune response and increased inflammation is a possible link between various physical diseases and stress, including cardiovascular disease, thyroid disease, and diabetes.

Impact of stress on daily activities

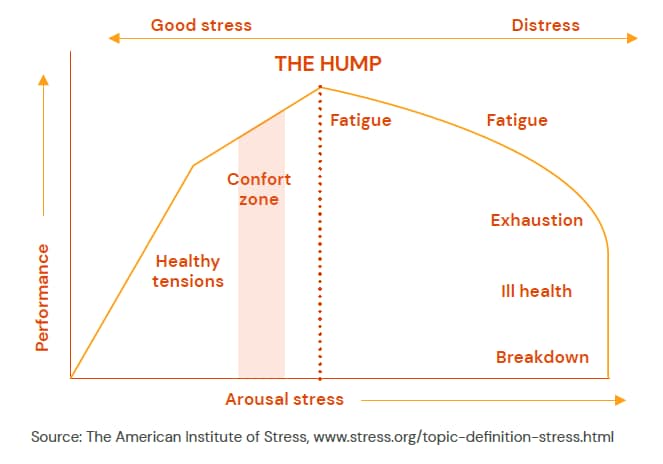

Initially increasing stress, or arousal, increases performance, this is explained by the Yerkes-Dodson Law (see diagram).

The ‘comfort’ zone allows you to work under stressful conditions. Levels of arousal or stress above the ‘comfort’ zone however, lead to impaired performance, reduced concentration and fatigue. If not addressed, prolonged chronic stress can lead to structural and functional changes inside the brain. These changes can play a role in the development of or trigger several physical and mental illnesses including:

- Depression, anxiety, schizophrenia

- Hypertension

- Cardiovascular diseases

- Endothelial dysfunction

- Sleeping problems.

How much stress is too much?

Stress is personal. What someone thinks is tressful, you might find satisfying and fun. For example, some people may find working 10 hours a day for long periods does not cause stress; for others, it will. Some people enjoy public speaking; for others, this can be stressful. There are many things that can cause stress. When they do, we call them ‘stressors’.

Potential stressors include:

- Relationship difficulties

- Work issues

- Life changes (e.g. marriage, separation, retirement, moving house, starting a new job, financial stress, being retrenched or becoming unemployed)

- Illness

- Study demands

- Event planning (e.g. holidays and family events)

- Becoming a new parent

And the list goes on. Your stressors will also change over time as your life demands change. Recent studies have found genetic differences in the genes that direct the production of stress hormones, and that there are differences in the way stress impacts on these genes. This may be the reason why people respond differently to stress, and why some are more vulnerable to the effect of chronic exposure to stress.

Stress and mental health

There’s a common misconception that there is a direct correlation between stress levels and mental health. There has been an assumption that if we want to improve mental health, and particularly mental health at work, we need to reduce stress. However, the research shows that the factors affecting our mental health are much more complex and interlinked than this simplistic model.

Our mental health and wellbeing is impacted by:

- Individual factors: personal resilience, genetics, early life events, personality, mental health history, lifestyle factors.

- Home/work factors: conflicting demands, significant life events.

- • Workplace factors: the design of our jobs, the teams we work in and the culture of an organisation.

Managing stress

It’s important to remember that stress is more than just feeling overworked. We have become accustomed to feeling high levels of stress and hence are often unaware of or may not even know what it feels like to be relaxed. You need to be able to recognise stress to deal with it. By repeating these 4 steps regularly, you may start to recognise your stressors.

1. Event: Describe to yourself one event this week that you found stressful. Consider where you were, when it was, who was there and what you were doing.

2. Rating: On a scale of 1-5, how stressful was this event? (1 = mildly stressful, 5 = extremely stressful)

3. Thinking: What were you thinking about this event? For example, were you thinking of the worst possible outcomes? Were you focusingon the stress itself?

4. Feeling: Where did you feel the stress? For example, as a physical ache or more emotional response, such as making you irritable? Did it change the way you were thinking, e.g. less able to concentrate or change your behaviour, such as disturbing your sleep?

It is helpful to develop a range of responses to stress. Luckily, there are some tried-and-true strategies for dealing effectively with the stress that shows up in our lives.

1. Recharge activities: When we get stressed, we often stop making time for things that are nourishing, satisfying and refreshing to do. This can include looking after our physical wellbeing (eg. eating well and getting enough hours of sleep) or psychological wellbeing (spending time with loved ones, engaging in hobbies).

2. Daily routines: The human mind likes predictability and certainty. When life gets stressful, we can restore some order to the chaos by ensuring that we continue with simple daily routines.

3. Circles of concern and influence: The problems, issues and difficulties we face generally fall into two ‘circles’:

• Circle of concern contains things over which you have little direct control.

• Circle of influence contains those concerns that you can actually do something about –focus on making changes in this circle.

4. Reality check: As mentioned before, stress has a large ‘thinking’ component, and certain types of thinking are likely to trigger stress and/or make your stress worse. Thought challenging is a useful strategy to ensure the way you are thinking about a situation is more balanced, realistic and helpful.

5. Physical Exercise: Exercises reduces cortisol/adrenaline in the body, and stimulates the body’s production of endogenous opioids (e.g. endorphins).

Key messages

- Stress is a normal condition, not a mental illness.

- Everyone experiences stress, but we experience it differently and this changes over time.

- Prolonged stress can negatively impact physical and mental health.

- Learn to recognise your stressors so you can deal with them.

- Reaching out to your current social support network, or building new social connections based on a shared identity or commonality can provide a buffer against the negative impact of stress on your mental health.

Resources

Factsheet: Mindfulness in everyday life

myCompass www.mycompass.org.au

For more information

Visit blackdoginstitute.org.au

Find @blackdoginst on social media